News

European FIUs Often Understaffed, Unequipped Against Financial Crime

European nations deemed most vulnerable to money laundering, terrorist financing and other financial crimes often do not staff and resource their financial intelligence units to levels that account for their exposure, data reviewed by ACAMS moneylaundering.com shows.

Having an FIU in place is one thing, but such agencies are also expected to operate apolitically and autonomously from their governments, and, according to the Financial Action Task Force, receive the “financial, human and technical resources” necessary to collect, analyze and distribute financial intelligence in a timely manner.

FATF uses several metrics to assess FIUs, from the technological, legal and administrative tools they have to fulfill their mission, to their ability to receive suspicious transaction reports, or STRs, in digital format and monitor large currency transactions.

“But the number of employees is a key indicator,” Yehuda Shaffer, former head of Israel’s FIU, told moneylaundering.com.

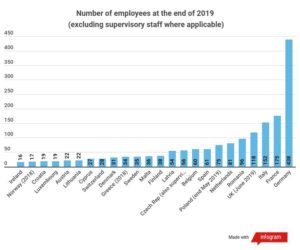

Against those criterion, and after adjusting for the size of their financial sectors, STR volumes and documented vulnerabilities to illicit finance as of 2019, the FIUs of Switzerland, which employed 28 individuals that year, Britain, which employed 118, and Ireland and Luxembourg, which employed 16 and 19 respectively, appear understaffed.

Demographics vary significantly across Europe: Malta, Luxembourg, Cyprus, Montenegro and Iceland each count fewer than 1 million residents while the populations of Italy, France, the United Kingdom and Germany all exceed 60 million.

Europe’s national FIUs also vary significantly in terms of workforce.

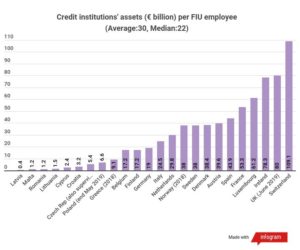

But population is a less than ideal metric with which to compare FIUs when considering that financial institutions in Luxembourg, which counts only 620,000 inhabitants, held €1.2 trillion in assets as of 2019, nearly matching the combined assets of banks in Greece, Romania, Poland and the Czech Republic, where together nearly 79 million individuals reside.

Comparing the number of employees of an FIU with the volume and aggregate value of its nation’s financial transactions is perhaps the quickest method to identify a short-staffed agency, particularly so with Switzerland, one of the world’s premier financial centers.

Swiss banks and other financial institutions had €3 trillion in assets on the books by the end of 2019, while Switzerland’s financial intelligence unit, MROS, employed only 28. Those figures break down to more than €109 billion per FIU employee, more than tripling the continental average.

The United Kingdom, where banks held €7.8 trillion and UKFIU employed 118, and Ireland, whose FIU employed 16 individuals while banking assets exceeded €1.2 trillion, complete the podium of European nations with apparently understaffed FIUs.

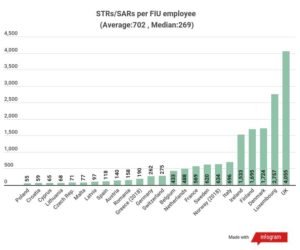

FATF identifies reception, analysis, and dissemination of financial intelligence as the primary tasks of an FIU, and comparing the staffing numbers of each agency against the volumes of reports they process in a typical year unearths significant discrepancies.

An employee of Poland’s General Inspector of Financial Information, for example, managed an average of 55 STRs in 2019, while his counterpart in Ireland dealt with more than 1,200.

Employees of Luxembourg’s Cellule de Renseignement Financier and Denmark’s Money Laundering Secretariat processed more STRs on average than their counterparts across Europe, according to the data, which moneylaundering.com obtained from FATF and annual disclosures by the FIUs, as well as via direct requests to those agencies.

With an average of more than 4,000 STRs for each employee, the United Kingdom’s FIU again placed first in a competition where last wins the prize.

UKFIU’s shortcomings have already drawn criticism from FATF, which, after evaluating Britain’s defenses against financial crime in March 2018, noted that the British government deliberately limits the agency’s role in “operational and strategic analysis.”

“The UKFIU suffers from a lack of available resources (human and IT) and analytical capability, which is a serious concern considering similar issues were raised over a decade ago,” FATF found. “The limited role of the UKFIU calls into question the quality of financial intelligence available to investigators.”

U.K. law enforcement agencies instead use their own resources to review suspicious activity reports, or SARs, according to FATF, but not enough to compensate for UKFIU’s lack of analysis.

MROS, Switzerland’s FIU, appears woefully understaffed against the country’s enormous, outsized financial sector, but ranks near the middle in terms of reporting volumes, with 275 STRs per employee in 2019. However, this result must be viewed against a backdrop of general reticence by Alpine institutions to flag suspicious activity after decades of bank secrecy.

“Reporting by financial intermediaries is limited, occurring mainly when there are grounded suspicions,” FATF found in 2016. “Financial intermediaries are not putting into practice the broader interpretation of the reporting requirement promoted by Swiss authorities” and “the number of failures to meet the reporting requirement seems to be underestimated.”

FATF’s criticism did not go unheard in Switzerland, where anti-money laundering and reporting expectations have risen, at least on paper.

“FATF’s push for more reports caused an increase in STRs, many of which are poor and add to the current backlog,” said Stiliano Ordolli, former director of the Swiss FIU. “Since then, the FIU has been understaffed and hiring new recruits could prove to be in vain if useless STR volumes keep rising.”

More risk, fewer employees

Viewed from the context of STR volumes and total assets, the FIUs of Switzerland, the United Kingdom, Ireland, Luxembourg, Finland and Denmark may appear neglected to some. Others would argue that the size of an FIU should instead primarily be governed by each nation’s unique, documented exposure to financial crime.

Such a view would benefit Denmark and Finland, where risk is limited, according to the Basel Institute on Governance, but would worsen the case for Switzerland, which ranked third among the 24 European nations moneylaundering.com compared for their vulnerability to illicit finance, as well as for Luxembourg, which ranked sixth.

The Basel Institute ranked Cyprus and Italy first and second in 2019, with Latvia and the Netherlands rounding out the top five.

“In the end, the U.K., Switzerland, Luxembourg and Ireland seem understaffed, and, as it happens, they are also major financial centers,” said Shaffer, the former head of the Israeli FIU.

Workloads also fluctuate between FIUs of different types. Such is the case with Malta’s FIAU, which has a supervisory role.

“Several FIUs are responsible for more than just the FIU function, and the demands that any extra function puts on its support team may vary significantly,” Alfred Zammit, deputy director of the FIAU, told moneylaundering.com.

Information technology has become an indispensable component of an effective FIU, as FATF noted after evaluating the United Kingdom. But London’s deficiencies in this area are not unique: Up until last year, when Switzerland’s MROS adopted the goAML tool developed by the United Nations, the agency used 1990s software that required staff to input data manually.

The origin of STRs also plays a role, nowhere more so than in Luxembourg. The Grand Duchy serves as PayPal and Amazon’s financial hub in Europe and must therefore handle all STRs those firms file from anywhere on the continent, regardless of their relevance.

Attacking the problems of inefficacy and inefficiency with a hiring campaign does not always work. The staff count of Germany’s FIU, for example, rose from 19 employees in 2010 to more than 400 a decade later, but results did not follow.

The agency has accumulated multiple backlogs of thousands of STRs since moving from the federal police to the Finance Ministry’s customs branch in June 2017, been accused of ignoring signs of massive fraud at Wirecard, the now-defunct payment processor, and was even the target of a police raid last year after allegedly withholding financial intelligence.

“Although the number of staff increased tenfold, the results didn’t rise in proportion because of a problematic reform that shows the effectiveness of an FIU is also a question of experience, competence and good relations with the police and judicial authorities,” Ordolli, the former head of MROS, told moneylaundering.com.

Scandals, then hires

The data reviewed by moneylaundering.com shows that many nations at the center of recent high-profile financial scandals, including Malta, the Baltic states and Cyprus, now have well-staffed FIUs.

The FIAU of Malta, a country long plagued by financial crime at home as well as from abroad, jumped from 19 employees in 2014 to 70 by the end of 2019.

In Latvia, home of the now-defunct ABLV Bank, the FIU tripled in size from only 18 employees in 2018 to 54 by 2019. Switzerland’s FIU, MROS, welcomed 12 recruits in 2020 to increase its staff to 40, and plans to hire 10 more employees after updates to the country’s AML regime.

Hiring fever has spread across Europe. The FIU of Cyprus recruited three financial analysts and one lawyer in 2019, Sweden’s FIU added 20 specialists and now boasts a staff of 55.

France’s Tracfin added 15 fulltime positions in 2020 and aims to hire five additional staff, while Poland’s 2019 national risk assessment indicated that the country’s FIU would hire 24 recruits in the near future to reach 100 employees.

UKFIU’s staffing levels increased from 80 at the time of FATF evaluation’s in 2018, to 118 by the end of 2019.

The boosts promise to make the reception, analysis and distribution of financial intelligence more effective in Europe, but whether those countries have the political will to develop that information into criminal cases and stronger enforcement is another question altogether.

“Increasing resources produces few results if the FIU does not have operational autonomy, especially in smaller countries where everyone knows each other and political pressure is stronger,” Ordolli said.

Contact Gabriel Vedrenne at gvedrenne@acams.org

| Topics : | Anti-money laundering , Counterterrorist Financing |

| Source: | European Union , Germany , Switzerland , Luxembourg , United Kingdom , Malta , Cyprus , Poland , France |

| Document Date: | March 19, 2021 |