News

Suspicious Activity Reporting Varies Significantly Across Europe

Suspicious transactions reports, or STRs, and suspicious activity reports, or SARs, are among the few standard indicators available for measuring the extent of financial crime in a country. Those with larger financial sectors typically record higher volumes of SARs and STRs each year.

But this logic has its exceptions in Europe, where reporting has reached record volumes but still varies significantly among the 12 largest nations in terms of banking assets—including the United Kingdom, France, Germany, Switzerland, Luxembourg and the Netherlands—and not always in proportion to the size of their financial markets.

“Reports are an indication of the importance of anti-money laundering and counterterrorist financing in a country,” Alain Curtet, a lawyer in Paris, told ACAMS moneylaundering.com. “It’s the impact of the local regulatory authority taking regulations into account: The more active it is, the more STRs there are, because actors cannot afford to be punished.”

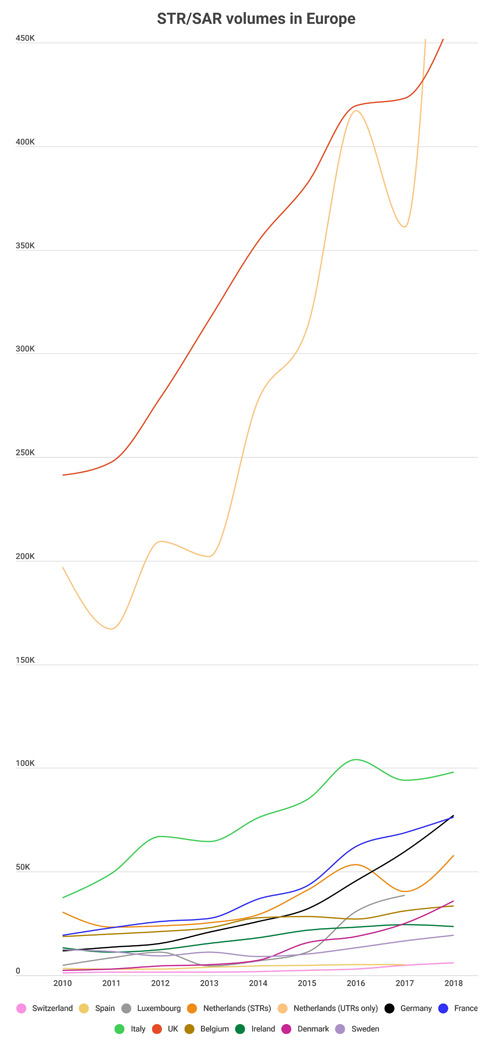

The total number of STRs and SARs filed by financial institutions and other regulated entities in the 12 largest European nations doubled from almost 560,000 in 2010 to more than 1.1 million in 2017, and is on track to exceed 1.6 million for 2018.

Denmark, where reporting numbers grew almost 10-fold, experienced the most pronounced increase, followed by Luxembourg and Germany, where volumes rose more than eightfold and fivefold respectively.

Sweden, Spain and Belgium saw the smallest increases, at 35, 58 and 66 percent.

A preponderance of financial scandals illuminated by the Swiss Leaks, Panama Papers, Paradise Papers and other confidential records may have helped drive reporting volumes upward.

Legal and regulatory reforms EU nations have made in the past four years to comply with the Fourth Anti-Money Laundering Directive, or 4AMLD, also played a role, Maria Evstropova, director of regulatory consulting with Duff & Phelps in London, told moneylaundering.com.

In Luxembourg, for example, regulators have moved from a somewhat cautious and restrained approach towards more assertive intervention, Evstropova said, while in Germany, “the threshold for reporting previously required a high degree of certainty of an offense.”

Explanations

A side-by-side comparison of STR volumes on its own, however, gives an incomplete picture, as only 600,000 people live in Luxembourg while 82 million live in Germany.

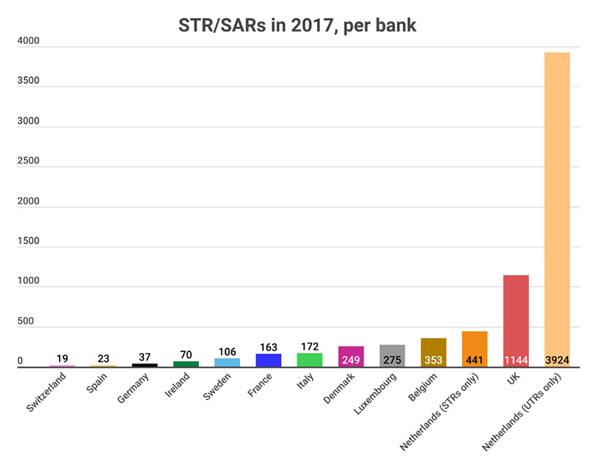

The European Banking Federation, a trade group in Brussels, uses two datapoints to improve the comparison: number of banks and total banking assets. In the end, the larger a country’s financial system, the more STRs or SARs its financial intelligence unit, or FIU, should receive.

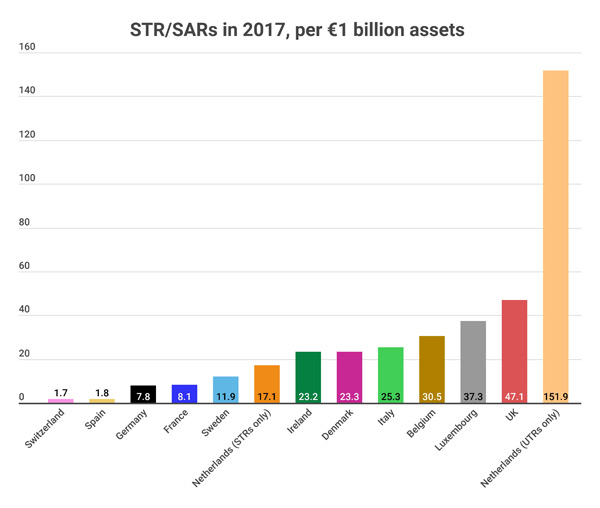

Using this methodology shows that reporting volumes in Italy and Ireland were in line with the size of their financial sectors in 2017 while those in Switzerland, Spain, the Netherlands and the United Kingdom were out of phase, sometimes for opposing reasons.

Financial institutions in Switzerland, Europe’s fifth-largest market by banking assets, appear to have underreported suspicious activity. The country’s FIU received only 1.7 STRs per €1 billion of banking assets in 2017, roughly a quarter the rate of France and Germany.

The United Kingdom stands out at the other end of the spectrum after receiving 47 STRs per €1 billion of assets in 2017, a rate six times higher than that of France and Germany. Luxembourg placed second at 37 STRs per €1 billion.

The Netherlands recorded the highest filing rate per bank and per assets if more categories of reporting are considered: Dutch institutions must flag any transaction that on its surface appears “unusual,” leaving it to their country’s FIU to identify truly suspicious activity.

Without taking Dutch unusual transaction reports, or UTRs, into account, the average filing rate for the 12 largest European financial markets in 2017 hovered around 254 reports per bank in 2017 and 20 reports per €1 billion in banking assets. Including unusual transactions skews the rates to 545 per bank and 31 per €1 billion.

Switzerland’s longtime role as a secretive financial haven and perceived lack of focus on illicit finance contribute to the low number and frequency of reports, but, according to Evstropova, bankers “may file a low number of SARs, but our experience shows that where there is a suspicion, firms may take steps and exit the relationship.”

“The country’s historical position is changing, and we may see the same increase in SARs in the coming years as we have seen in Luxembourg,” Evstropova said.

Following Switzerland’s evaluation by the Financial Action Task Force, or FATF, in 2016, and spurred by the Panama Papers and Swiss Leaks, national authorities began taking measures to preserve their country’s reputation and keep it from being blacklisted as a tax haven.

Swiss lawmakers this autumn will review plans to close loopholes identified by FATF, including a proposal to extend due diligence obligations to financial intermediaries and persons providing services in connection with companies or trusts.

A third proposal would require banks to review and update their know-your-customer files more frequently, a fourth would lower the threshold at which firms involved in the precious metals trade must vet their clients.

AML enforcement may remain comparably low in Switzerland but the country’s adherence to bank secrecy is not ironclad. In July 2018, the Swiss Supreme Federal Court allowed tax authorities to pass data on some 40,000 accounts at UBS to France despite strong opposition from bankers and the Alpine nation’s leading political party.

Swiss financial institutions must only report transactions based on a “grounded suspicion” and tangible evidence linking the funds in question to a crime—a generally higher threshold than other nations use.

Swiss authorities now encourage financial institutions “to make more use of their right to report” at a lower threshold, said Serge Steiner, a spokesperson with the Swiss Bankers Association.

The high filing rates of the U.K. and the Netherlands are more likely an outcome of perceived regulatory and legal expectations than a general enthusiasm for reporting.

Overreporting has negative consequences of its own. British financial institutions in particular have drawn criticism from FATF for overwhelming their country’s FIU and investigators with large quantities of defensive SARs of negligible intelligence value.

Contact Gabriel Vedrenne at gvedrenne@acams.org

| Topics : | Anti-money laundering , Counterterrorist Financing |

| Source: | European Union , United Kingdom , Switzerland , France , Netherlands , Germany , Luxembourg , Spain , Belgium , Italy |

| Document Date: | August 28, 2019 |