News

In 2019, Europe Entered New Era of AML Enforcement

2019 was a remarkable year for Europe in terms of anti-money laundering and sanctions enforcement, marked by Transatlantic cooperation against illicit finance, a high-profile banishment from the Baltics and record penalties in France.

Three of the five AML penalties imposed by France’s Prudential Supervision and Resolution Authority, or ACPR, last year targeted money services businesses, led by the record €1 million penalty against Western Union in January. ACPR cited the U.S. MSB for failing to fully vet high-risk clients and flag suspicious activity to Tracfin, the country’s financial intelligence unit.

In February, a high court in Paris set a milestone of its own by siding with the Parquet National Financier, or PNF, in fining Swiss lender UBS a record €3.7 billion as part of a “convention judiciaire d’interet public,” or CJDP, a relatively new mechanism that operates similarly to a U.S. deferred prosecution agreement, for hiding and laundering billions of euros in taxable income for French clients from 2004 to 2012.

In August, Peter Braunwalder became the first banker in France to avoid jailtime under a similar mechanism, a “comparution sur reconnaissance prealable de culpabilite,” or CRPC, after pleading guilty to unlawful financial solicitation and laundering the proceeds of tax fraud, and paying a €500,000 fine.

His former employer, HSBC Private Bank, agreed three years earlier to pay French authorities more than €300 million to avoid trial as part of a CJDP.

“French banks have much more experience against money laundering and feel secure, but need to review their methodologies,” said William Feugere, an attorney who oversees compliance and business ethics for the Paris Bar Association. “The past year has shown that they must increasingly integrate other forms of compliance, such as anti-corruption and data protection.”

However, despite ACPR’s insistence that financial institutions stay vigilant over their foreign operations, the message did not seem to take hold in 2019, Feugere said.

“They have not yet fully integrated the fact that most often the danger doesn’t come from the group but from a subsidiary,” Feugere said. “It is therefore necessary to carry out due diligence even with distant entities, which are often the most difficult to control and money launderers know this.”

Belgian prosecutors announced a record resolution of their own against HSBC in August, pursuant to which the Swiss lender agreed to pay €294 million to avoid trial for allegedly engaging in tax fraud and money laundering.

Europe’s perhaps most notable enforcement action of 2019 occurred in Estonia, where the Financial Supervisory Authority ordered the local branch of Danske Bank, Denmark’s largest bank by assets, to pack up and leave after accusing the lender of engaging in “profound and material” AML violations that “seriously damaged” the Baltic nation.

Danske Bank withheld data on suspected money laundering and “to a very large extent” misled authorities as to the scale of its exposure to financial criminals, according to the FSA.

The case caused friction between the Estonian regulator and Denmark’s own FSA, with each accusing the other of either missing or ignoring indications of illicit finance at Danske Bank over a period of several years.

“As the parents of our visitor do not wish to be involved in dealing with it, we are politely sending the visiting bank home because not only has that guest acted rudely, it has also smashed some valuable possessions belonging to its host,” Estonia’s FSA said.

The European Banking Authority investigated both agencies over their handling of Danske Bank but drew sharp criticism from senior EU officials and lawmakers after dropping the probe in April without making any conclusions.

United Kingdom

The U.K. Financial Conduct Authority was running more than 60 AML investigations as of July 2019 but disclosed only one major AML-related penalty for the entire year.

Standard Chartered Bank consented to pay £102 million to the FCA in April to resolve “significant shortcomings” in its U.K. correspondent banking operations and governance of its branches in the United Arab Emirates.

From 2009 to 2014, the London-based lender failed to apply U.K.-equivalent standards in the UAE, according to the FCA, which cited “serious and sustained” weaknesses in the bank’s due-diligence and transaction monitoring, as well as in its approach towards identifying and mitigating risks and communicating them to senior managers.

The £102 million fine is the second-highest AML-related financial penalty ever imposed by the FCA, and came as part of a joint investigation with state and federal authorities in New York that resulted in a total outlay of roughly $1.1 billion and an extension of the terms of the lender’s 2012 deferred prosecution agreement.

Anna Bradshaw, a partner with Peters & Peters in London, told moneylaundering.com in an email that the most notable aspect of the case was not the significant size of Standard Chartered’s penalty, but the fact that the FCA levied it in conjunction with the U.S.

“The FCA’s involvement in the settlement may have taken the edge off criticism which may otherwise accompany fines that the U.S. imposes on non-U.S. institutions in amounts that far exceed those that could be expected from local regulators,” Bradshaw wrote. “It is still too early to say whether this is part of an ongoing effort by the U.S. to involve foreign regulators more.”

Zia Ullah, head of corporate crime and investigations at Eversheds Sutherland in London, told moneylaundering.com that the FCA tended to investigate suspected breaches of due-diligence obligations in 2019, including those pertaining to ongoing monitoring and deeper vetting of clients that pose a higher financial-crime risk.

“Cases we’ve looked at usually related to high-risk customers, such as PEPs [politically exposed persons], and latterly more focus on screening systems and controls, and transaction monitoring,” Ullah said. “Those are really the areas where we’ve seen the sharpest focus.”

The FCA meanwhile continued to emphasize its intention to pursue criminal cases against financial institutions or senior employees responsible for egregious AML violations.

Mark Steward, the FCA’s head of enforcement, told an industry event in London in April that the regulator had a large number of live investigations, including into “suspected significant AML systems and control issues,” and wanted to identify a suitable target for the U.K.’s first criminal case involving AML violations.

But the Gambling Commission was again the most prolific AML regulator in Britain last year in terms of the volume of enforcement actions brought, having disclosed penalties against 10 gaming firms and collected almost £16 million in fines and other enforcement-related payments, down from £24 million in 2018.

HM Revenue & Customs, the U.K. tax authority, also stepped up AML enforcement in 2019, culminating with its record £7.8 million penalty against Touma Foreign Exchange, a money services business in London, in September.

From June 2017 to September 2018, the MSB failed to assess, document and control risks posed by financial criminals, establish AML policies, train staff for compliance purposes and meet customer due-diligence obligations, HMRC found.

The penalty against Touma Foreign Exchange came weeks after the FCA, London Metropolitan Police and HMRC raided 12 MSBs in west London amid concerns that the sector remains vulnerable to organized crime and vast money laundering operations.

The U.K. Serious Fraud Office, or SFO, did not issue any blockbuster penalties in 2019.

In July, the agency entered into a deferred prosecution agreement, or DPA, with Serco, which required the U.K. outsourcing giant to pay a penalty of £19.2 million and cover the SFO’s investigative costs of almost £4 million, for fraud and false accounting related to a contract with the U.K. Justice Ministry.

The SFO that month also struck a DPA with Sarclad, a U.K. metals manufacturer, which included a £6.5 million disgorgement and a £352,000 penalty, and five months later entered into a DPA with Guralp Systems, a U.K. provider of seismic instrumentation, for bribery. The settlement included a £2 million disgorgement but no penalty.

But the SFO came under fire for failing to pursue or obtain convictions against senior employees implicated in wrongdoing by corporates which had entered into DPAs.

“2019 was a year of mixed successes and failures for the SFO,” Christopher David, an attorney with WilmerHale in London, wrote in an email to moneylaundering.com. “The successes, from the SFO’s point of view, were the increase in DPAs, but there remains significant concern about the SFO’s ability to secure convictions against individuals, with or without a DPA.”

In June, a court ordered FH Bertling, a U.K. logistics group, to pay a £850,000 fine for paying bribes to secure a shipping contract in Angola. In November, the U.K. subsidiary of French transport conglomerate Alstom was fined £15 million and ordered to pay £1.4 million in costs for paying bribes in Tunisia.

SFO chief Lisa Osofsky publicly stressed the agency’s determination to work in concert with its international counterparts and expedite investigations.

The agency also issued guidance outlining what it expects from businesses seeking leniency at the conclusion of an investigation.

The publication marked a significant change from the SFO’s approach under Osofsky’s predecessor, David Green, who had repeatedly stated that the agency “did not do guidance” and fashioned it solely as a “pure investigator and prosecutor,” David, the London-based attorney, said.

“Most importantly, it confirms the SFO welcomes corporate cooperation,” he said.

The Netherlands

Banks in the Netherlands at the beginning of the year were still reeling from the record €775 million penalty and disgorgement ING, the country’s biggest lender by assets, paid in September 2018 after admitting to AML compliance deficiencies that allowed criminals to launder hundreds of millions of euros.

Dutch prosecutors accused the Amsterdam-based bank of failing to adequately fund and staff its AML program for several years – a message which saw other Dutch banks start allocating huge sums towards improving their compliance systems and recruiting more staff.

De Nederlandsche Bank, or DNB, which supervises banks, money services businesses and other firms for AML purposes, did not disclose any AML-related actions last year because the relevant breaches occurred before July 2018, when Dutch law was amended to require the regulator to publish details of their enforcement.

DNB focused largely on monitoring the implementation of remediation programs previously agreed with several banks, the regulator claimed in its annual report for 2019.

“For many banks, these involve several years of substantial financial and human investment in order to rectify major shortcomings in, for example, customer due diligence and transaction monitoring processes,” DNB claimed.

The central bank also carried out various “institution-specific and thematic studies” into how financial institutions implement AML rules, but did not offer further details.

“In a number of cases, investigations led to interventions and formal measures,” the central bank stated in the report. “In addition to new shortcomings, we see that some institutions are once again falling into the same shortcomings, despite recovery previously enforced by DNB.”

DNB also held individual directors of institutions personally responsible, and, in a few cases, imposed “punitive measures” on an individual.

Annemarije Schoonbeek, a former manager with the Dutch Financial Markets Authority, told moneylaundering.com that the DNB emphasized the need for banks to continue improving their AML programs in 2019 and also stressed the importance of public-private partnerships aimed at tackling organized crime in the Netherlands.

“The pressure on remediation continues to be great and DNB is willing to take enforcement action against financial institutions in cases of serious findings, and if they don’t act quickly enough,” she said. “But on the other hand there is also a focus on doing it together in the interest of tackling serious crime, and you might say that those two things can be at odds.”

In August, Dutch lender ABN Amro disclosed that it had been ordered to rescreen all 5 million of its retail clients in the Netherlands for potential involvement in financial crimes and warned that ongoing investigations could conclude with penalties.

A month later, the Dutch Prosecution Service announced the launch of a criminal investigation into the lender for allegedly reporting suspicious transactions too late or not at all over a period of several years, as well as failing to monitor customers adequately and sever ties with suspicious clients quickly enough.

“Usually a criminal investigation, a measure of last resort, would be preceded by a financial institution having already been subject to informal or formal measures of a regulator and there’s been no improvement,” said Schoonbeek, now an industry consultant in Amsterdam.

Germany

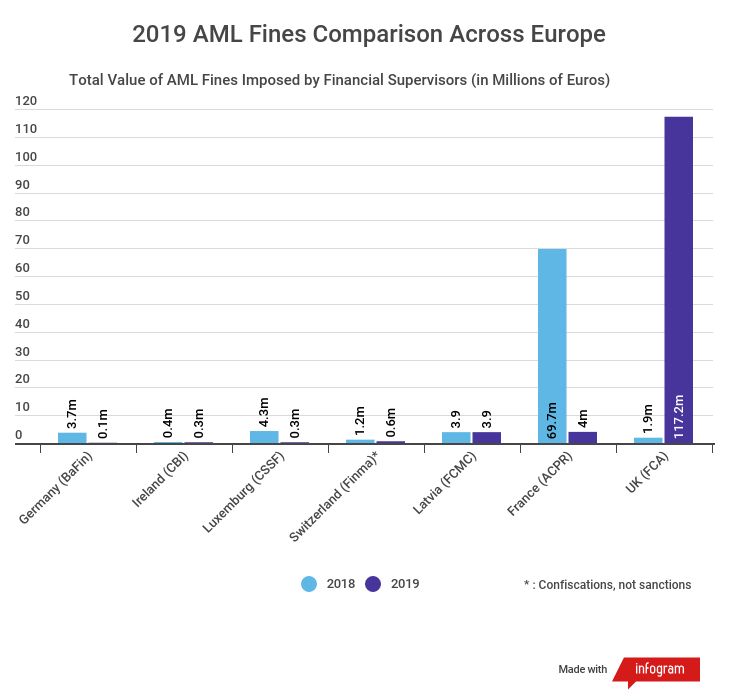

The Federal Financial Supervisory Authority, BaFin, issued 19 notices against persons subject to supervision under the country’s Money Laundering Act in 2019 and collected only €92,000, in penalties, down from the 19 notices issued in 2018 and sharply below the €3.7 million seized that year.

German authorities seized €50 million in property and other assets n February as part of their continuing investigation into the Russian Laundromat.

September was marked by the high-profile raid of Deutsche Bank’s headquarters in Frankfurt amid an investigation into the lender’s ties to the money laundering scandal that engulfed Danske Bank Estonia, followed by a raid of Commerzbank’s headquarters for its role in CumEx, a massive tax-fraud scandal.

Authorities then dismantled a hawala network of 27 individuals suspected of laundering more than €200 million.

In May, BaFin warned, but did not fine, N26, a digital bank in Berlin, for a panoply of compliance-related shortcomings, including know-your customer deficiencies, insufficient AML staff and failures to report suspicious activity.

“The biggest trend from my point of view is that money laundering is now more frequently used by the prosecution as a vehicle for confiscation,” Tobias Eggers, an attorney with Park Wirtschaftsstrafrecht in Dortmund, told moneylaundering.com. “What stands out really is the commitment [by authorities] to confiscate as much money as they can.”

Switzerland

Switzerland returned €380 million to Brazil throughout last year after linking the funds to corruption at Brazilian state-run energy firm Petrobras and Odebrecht, a global construction conglomerate, and seizing them from accounts at PKB Privatbank, Banque Heritage, the now-defunct Banca della Svizzera Italiana and other institutions.

August saw German authorities cooperate with their Swiss counterparts in seizing several luxury and sports cars from Khadem al-Qubaisi, former director of Abu Dhabi-based sovereign wealth fund IPIC, for his involvement in the embezzlement and laundering of billions of dollars from 1MDB in Malaysia.

A former Morgan Stanley banker received a 30-month sentence and a €2.8 million fine in October for helping a Greek politician launder bribes tied to a military contract, while Gunvor, a commodities trader, paid €90 million for similar infractions.

In November, two bankers who worked at Coutts & Company private bank in Zurich were fined for failing to report suspicious transactions tied to the 1MDB scandal.

The year ended with a court in St. Gallen rejecting Finma’s seizure of roughly €90 million from Banca della Svizzera Italiana 42 months earlier as part of the 1MDB investigation, and a Belgian lawyer receiving 30 months in prison for stealing hundreds of thousands of bearer shares from clients and laundering them into bank accounts throughout Switzerland.

“The positive is no major new cases broke out, some banks were involved in the Troika Laundromat or Russian Laundromat, but only marginally, and were dealt with by the regulator without sanctions so far,” said Emmanuel Genequand, a partner with PwC in Geneva.

Malta

Malta’s efforts to counter its reputation as a center for illicit finance encountered setbacks in 2019.

In August, a month after Malta’s Financial Intelligence Analysis Unit, or FIAU, fined Satabank a record €3 million for significant compliance deficiencies, Moneyval, the Financial Action Task Force’s representative in Europe, questioned the vigor with which Maltese authorities enforce AML rules and prosecute high-level money laundering, bribery and corruption.

In November, the European Central Bank censured Bank of Valletta for “severe shortcomings” in risk management.

Investigators questioned Keith Schembri, Prime Minister Joseph Muscat’s chief of staff, on suspicion of involvement in the murder of Daphne Caruana Galizia, a journalist who was investigating high-level financial crimes at the time of her death. Schembri resigned from the position in November.

“Our enforcement priorities were policy setting, governance and widening the spectrum of measures and sanctions that the Financial Intelligence Analysis Unit may impose for compliance breaches beyond pecuniary penalties,” said Alfred Zammit, the FIAU’s deputy director. “This was done for greater effectiveness and efficiency in increasing AML and CFT compliance.”

Asia, and Asia-Pacific

India’s financial intelligence unit fined Punjab National Bank $2 million in August for failing to flag an unknown quantity of suspicious transactions, submitting other reports incorrectly and neglecting to collect beneficial ownership details from customers from April 2016 to November 2017.

In November, the Reserve Bank of India fined Mehsana Urban Cooperative Bank $660,000 for failing to conduct know-your-customer checks and violating rules governing the provision of loans to the institution’s directors and other interested parties.

The Hong Kong Securities and Futures Commission fined Guosen Securities Brokerage Company $1.9 million in February for failing to monitor more than 100 clients who in 2014 and 2015 made third-party deposits that did not align with their previous financial patterns.

Two months later, the regulator banned the former head of the firm’s retail brokerage division from working in the industry.

Australia’s Transaction Reports and Analysis Center issued just one AML-related penalty in 2019, fining remittance firm Compass Global Holdings $160,000 fine for failing to comply with requirements to report international transfers in 2018 and last year.

Larger settlements are in the works, however. In November, AUSTRAC petitioned an Australian court to approve a civil penalty against Westpac Banking Corporation, which the regulator accused of failing to report billions of dollars or suspicious cross-border payments from 2013 to 2019, including many allegedly linked to child sexual exploitation.

Westpac, the country’s second-largest lender by assets, disclosed ongoing negotiations with AUSTRAC and warned investors to expect a record penalty of around $570 million.

Colby Adams, Kieran Beer, Larissa Bernardes, Laura Cruz, Leily Faridzadeh and Silas Bartels contributed to this article.

| Topics : | Anti-money laundering , Counterterrorist Financing , Sanctions |

|---|---|

| Source: | European Union , France , United Kingdom , United Kingdom: Financial Conduct Authority , United Kingdom: HM Revenue & Customs , Netherlands , Germany , Switzerland , Malta , India , Hong Kong , Australia , Australia: AUSTRAC , Estonia |

| Document Date: | April 27, 2020 |