News

US AML Enforcement Returned in 2018

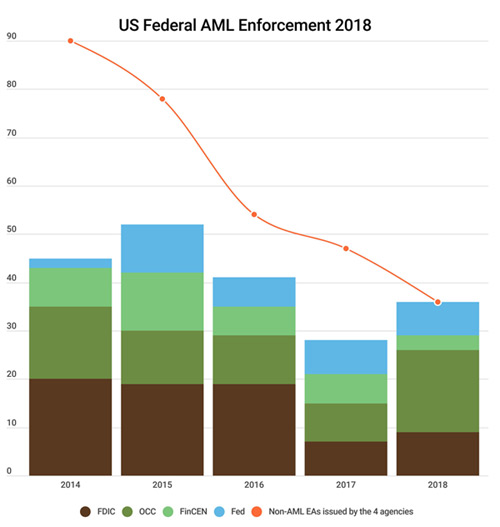

Federal enforcement of U.S. anti-money laundering rules jumped nearly 30 percent in 2018 after hitting record lows in each of the prior two years, according to data reviewed by ACAMS moneylaundering.com.

Nearly half of the 71 total enforcement actions issued last year by the Financial Crimes Enforcement Network, Office of the Comptroller of the Currency, Federal Reserve and Federal Deposit Insurance Corp., or FDIC, targeted institutions and individuals that violated AML rules, and roughly half of those AML-related actions came with monetary penalties.

Nearly half of the 71 total enforcement actions issued last year by the Financial Crimes Enforcement Network, Office of the Comptroller of the Currency, Federal Reserve and Federal Deposit Insurance Corp., or FDIC, targeted institutions and individuals that violated AML rules, and roughly half of those AML-related actions came with monetary penalties.

Led by the OCC’s extraction of $100 million from Capital One in October, the total value of AML fines assessed non-concurrently by federal banking regulators and FinCEN exceeded $307 million last year after hitting a 10-year low of $24 million in 2016, according to the data.

FinCEN assessed roughly $75 million in nonconcurrent AML penalties, including $5 million against Swiss lender UBS’ New Jersey-based brokerage, UBS Financial Services, for failing to implement an AML program designed to prevent clients from using securities accounts to move funds instead of make trades.

On Feb. 15, Minnesota-based U.S. Bank National Association agreed to pay $528 million to federal regulators and the Justice Department for manipulating its monitoring software to limit transactional alerts, short-staffing its compliance department, quashing internal dissent and withholding incriminating information from the OCC.

The Federal Reserve assessed a $15 million fine against U.S. Bancorp, the parent company of U.S. Bank National Association, and ordered the lender to give “adequate and complete responses to examiner inquiries” going forward.

Federal prosecutors and the OCC cited similar violations in disclosing roughly $369 million in fines and forfeitures eight days earlier against Rabobank. The Dutch lender’s California affiliate admitted to obstruction after executives concealed a third-party report from the national banking regulator in 2013.

In January, the Federal Reserve fined Taiwan’s Mega International Commercial Bank Co. $29 million for AML violations and deficient risk-management practices. The $81 million fine disclosed against Societe Generale in November for violating U.S. sanctions against Cuba represents the largest action concluded by the Fed in terms of value.

Several of last year’s enforcement actions show that many financial institutions still struggle at complying with transaction-monitoring requirements, limiting false-positive transactional alerts and reporting suspicious activity, said John Caruso, a New York-based principle for KPMG who specializes in regulatory enforcement and compliance.

“For the most part regulators look at what’s already in place, and what is in place hasn’t changed much—scenario-based monitoring with thresholds,” Caruso said. “Questions of data quality … are also now a standard part of regulatory focus.”

The New York State Department of Financial Services, or DFS, collected the most AML-related penalties in the United States for the third year in a row, led by the $420 million assessed against Societe Generale as part of the total $1.3 billion in outlays the French lender made to the state regulator, the Justice Department, the Treasury Department’s Office of Foreign Assets Control, or OFAC, and the Fed.

DFS began 2018 with a penalty against Western Union, tagging the global money services business with $60 million in outlays for, among other violations, failing to report hundreds of millions of dollars in remittances to suspected human traffickers in China and take action against the agents who handled those payments.

Some of those violations fueled Western Union’s $586 million settlement with federal regulators and prosecutors one year earlier, in January 2017.

DFS also fined Mashreqbank $40 million for AML, sanctions and recordkeeping violations, and ordered the Emirati lender to hire a new external auditor after concluding that bank executives did not adequately supervise a previous third-party AML consultant.

“One of the reasons you’re seeing heightened enforcement in the transaction-monitoring area is because it is among the most expensive and difficult requirements for banks [and other financial institutions] to get right,” said Alma Angotti, a former senior enforcement counsel for FinCEN. “You’re seeing data-quality issues, and failures to test and tune the rules you have in place.”

The FDIC concluded nine AML enforcement actions in 2018, none of which included a fine.

Singled out

The OCC was responsible for all eight of the AML-related enforcement actions issued by federal regulators against individuals in 2018, and all eight came with fines that together totaled $455,000.

Five of the actions targeted former senior employees of Merchants Bank of California, including a former chairman, director, chief banking officer and executive vice president.

Those executives pressured compliance staff to open accounts for high-risk clients, according to the OCC, which separately assessed a $35,000 penalty against Janet Chu, Merchants Bank’s former chief financial officer, for allowing a currency dealer to circumvent account-opening procedures.

Each of the 17 AML-related actions disclosed by the Financial Industry Regulatory Authority last year came with penalties, and 14 of them targeted individuals.

Finra assessed nearly $27 million in penalties in conjunction with those actions, including $140,000 from the former chief compliance officer and $115,000 from the former head of trading of Wilson-Davis & Co., a broker-dealer based in Salt Lake City.

In May, the industry regulator fined Industrial and Commercial Bank of China Financial Services, or ICBCFS, $5.3 million for a range of violations, including failing to build a system for flagging and reporting suspicious trades of penny stocks.

“Systems issues are a trend we continue to see in the AML space,” Susan Schroeder, Finra’s executive vice president of enforcement, told moneylaundering.com. “The second [trend] is failures in the penny-stock surveillance space—firms failing to appropriately surveil for potentially unregistered distribution.”

Finra’s action against ICBCFS was taken jointly with the Securities and Exchange Commission, or SEC, which fined the bank $860,000.

The SEC finalized nine other AML-related enforcement actions in 2018 and assessed a $60,000 penalty against the former AML compliance officer of Aegis Capital Corporation, a New York-based firm that failed to heed warnings of potential pump-and-dump schemes.

Citigroup agreed to pay the SEC $10.5 million in August to resolve a pair of enforcement actions that cited recordkeeping, accounting and supervisory deficiencies that resulted in $475 million of losses from loans that its Mexican subsidiary, Banamex, approved for Pemex contractor Oceanografia, or OSA.

“Many of the OSA work estimates were fraudulent and did not reflect amounts Pemex actually owed to OSA,” the SEC claimed.

Prosecutions and payments

Including its outlays from Rabobank, U.S. Bank and France’s Societe Generale, the Justice Department collected nearly $2.1 billion from firms involved in AML, sanctions and tax violations for the second-year running in 2018—two years after assessing just $785 million in tax-related penalties and no sanctions or AML penalties.

In November, MoneyGram agreed to forfeit $125 million to federal prosecutors in Pennsylvania for violating the terms of a 2012 agreement to avoid prosecution after agents of the money services business knowingly participated in schemes that defrauded customers.

Dallas-based precious-metals firm Elemetal LLC agreed to disgorge $15 million to federal prosecutors last year after pleading guilty to violating the Bank Secrecy Act, or BSA.

“In connection with Elemetal’s AML failures … hundreds of millions if not billions of dollars of laundered gold entered the U.S. financial system, including gold which represented the proceeds of international narcotic trafficking, foreign bribery, foreign smuggling, illegal gold mining, and U.S. Customs violations,” prosecutors claimed.

Prosecutors also claimed nearly $180 million in fines, forfeitures and restitution from five Swiss banks that helped Americans conceal taxable income: Basler Kantonalbank, Zurcher Kantonalbank, Bank Lombard Odier, Mirelis Holding and NPB Neue Privat Bank.

On a separate note, federal efforts to coordinate with financial institutions in identifying attempts to launder fraud proceeds through money-mule accounts have seen positive results, Steven D’Antuono, head of the FBI’s financial crimes section, told moneylaundering.com.

“The identification is really having financial institutions explain what they’re seeing in a [suspicious activity report, or SAR] narrative … and putting key words into BSA filings so we can cull that information and search for it more easily,” D’Antuono said.

OFAC collected more than $59 million combined from Societe Generale and JPMorgan Chase in 2018 after having assessed only one penalty against a lender the previous year: Canada’s TD Bank.

All quiet on the northern front

The Financial Transactions and Reports Analysis Centre of Canada, or Fintrac, did not issue any AML enforcement actions again in 2018, the second full year after a high court ruled that the agency’s allegedly opaque method of assessing penalties unfairly blocked firms from challenging its decisions.

Fintrac has not disclosed any administrative penalties or enforcement actions since the ruling, which the Federal Court of Appeals handed down on May 11, 2016.

Canada’s Department of Finance proposed a broad overhaul of the country’s AML regulations in June that would establish tighter deadlines for reporting suspicious activity and more stringent rules for vetting and monitoring politically exposed persons.

The revisions would also extend AML requirements to prepaid cards and cryptocurrency exchanges, as well as to title insurance firms to combat the flow of illicit funds into Canadian real estate.

In October 2018, Fintrac’s director disclosed plans to publicly outline how the agency calculates fines in an apparent effort to revive its authority to enforce AML regulations.

Fintrac published those policies four months later, on Feb. 7.

“I think the agency has had a reputation of being a difficult regulator and very technical in its compliance exams,” Jackie Shinfield, an attorney with Blake, Cassels & Graydon in Toronto, said. “Now they’re trying to send a new message that it’s [about] the effectiveness of your program.”

Fintrac also clarified when financial institutions should report suspicious transactions in the Feb. 7 guidance.

“Their interpretation is consistent with the standard of ‘reasonable grounds to believe’ … which is a pretty low threshold to file—and the guidance makes that clear,” Shinfield said. “These types of changes in general can only lead to a propensity to over-file.”

Canada’s Department of Finance unveiled plans last year to allocate tens of millions of dollars in additional budget to Fintrac, and more staff to enforce AML rules and process financial intelligence.

But the failure of a broad investigation into money laundering through British Columbian casinos in the final months of 2018 left some doubting Canadian authorities’ ability to tackle financial crime.

Colby Adams, Kieran Beer, Larissa Bernardes, Laura Cruz, Leily Faridzadeh and Silas Bartels contributed to this article.

| Topics : | Anti-money laundering , Counterterrorist Financing , Sanctions |

|---|---|

| Source: | U.S.: OCC , U.S.: OFAC , U.S.: Federal Reserve Board , U.S.: FinCEN , U.S.: Finra (NASD/NYSE) , U.S.: NYS Department of Financial Services , U.S.: FDIC , Canada: FINTRAC , U.S.: Department of Justice |

| Document Date: | April 5, 2019 |